ACCOGLIENZA E ARTE NELLE CORSIE SISTINE DI SANTO SPIRITO IN SASSIA

Renata Cristina Mazzantini

“Nessun luogo è senza un genio”, scriveva Servio Mario Onorato nel Commento all’Eneide, riferendosi al genius loci che in epoca romana era la personificazione di uno spirito che rappresentava l’identità di un luogo. Il genius loci allora era considerato un essere soprannaturale, una divinità di ordine minore, che incarnava la sacralità del luogo, lo tutelava e doveva essere oggetto di culto affinché si dimostrasse favorevole agli abitanti.

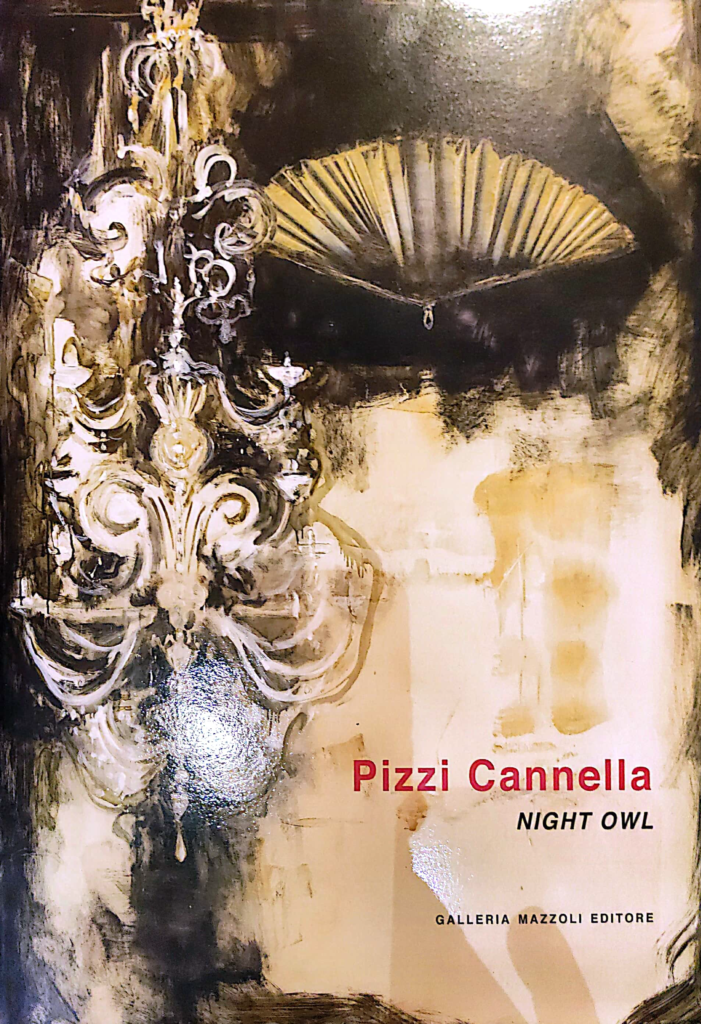

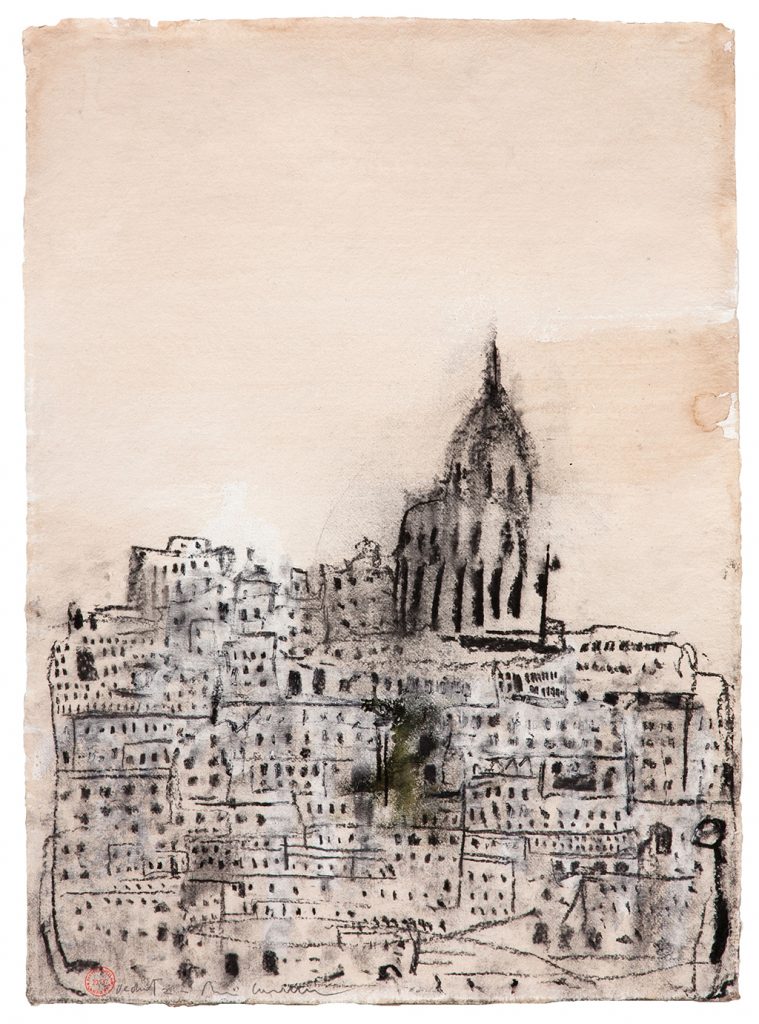

Il sentimento del genius loci è sopravvissuto a lungo e, anche se la vicinanza spirituale tra uomini e luoghi si è in parte perduta, a Roma lo si può tuttora avvertire annidato nel tessuto urbano, persino nel paesaggio artificiale della città, che è antico e denso di stratificazioni storiche. Ripensando alla suggestione esercitata dal concetto di genius loci, l’idea di allestire la mostra “Le Migranti” di Pizzi Cannella ai margini della città papale, all’interno del complesso ospedaliero di Santo Spirito in Sassia, più precisamente nelle magnifiche Corsie Sistine, può sembrare tanto affascinante quanto indovinata. Le Corsie Sistine, che costituiscono a Roma il primo esempio di architettura civile del Rinascimento, sono i due bracci simmetrici di un’imponente galleria lunga 130 metri.

Un volume architettonico poderoso impreziosito da 1.200 metri quadrati di affreschi, sovrastato da una copertura lignea piana e diviso da un elegante ciborio rinascimentale. Nonostante questa straordinaria spazialità, non è il pregio architettonico ma lo spirito del luogo, la sua vocazione storica all’accoglienza e il suo significato simbolico, legato alla caritas cristiana, a rendere Santo Spirito in Sassia un luogo ideale per ospitare la mostra del ciclo “Le Migranti”. Un ciclo di 99 tele dipinte da Pizzi Cannella dieci anni fa, con l’intento di stimolare una profonda e colta riflessione sulla migrazione, descritta non come emergenza ma come realtà storica, indissolubilmente legata al tema dell’accoglienza. Santo Spirito in Sassia, infatti, è un luogo privilegiato dell’accoglienza. Ha svolto e tramandato, sino agli anni ottanta del Novecento, la sua originaria funzione di assistenza e cura delle persone: prima dei pellegrini, poi dei trovatelli e infine dei malati. L’attuale complesso architettonico sorge sulla Schola Saxonum, costruita per volere di Ine, re del Wessex nell’VIII secolo, proprio con lo scopo di assistere e ospitare i viaggiatori anglosassoni in pellegrinaggio nella città santa. Allora a Roma la presenza di comunità straniere era numerosa e le Scholae svolgevano un ruolo assistenziale, dando vitto, alloggio ed eventualmente piccole elemosine ai pellegrini della propria etnia. Va ricordato che, insieme con i pellegrini, questi ospizi accoglievano anche malati e invalidi, indigenti e vagabondi in una difficoltosa promiscuità, dove sanitas corporise salus animae, quindi finalità caritativa e terapeutica, si confondevano costantemente.

Nel 1198 la Schola Saxonum, già divenuta hospitalis Anglorum ovvero ospizio dei pellegrini sassoni, fu trasformata da papa Innocenzo III (1198-1216) nell’Arcispedale di Santo Spirito in Saxia. Con il sostegno economico del sovrano britannico Giovanni senza Terra, il pontefice avviò la costruzione di un complesso architettonico per accogliere i bambini abbandonati o bisognosi e ne affidò la gestione all’Ordine Ospitaliero del Santo Spirito, il primo ordine ospedaliero non militare costituito con l’impegno esclusivo della caritas. Nel XV secolo la riforma ospedaliera sostituì ovunque, a poco a poco, la carità con il sapere medico. Così Sisto IV della Rovere, che fu papa dal 1471 al 1484, decise di rifondare completamente Santo Spirito in Sassia, concludendone la costruzione nel 1478. Per rafforzare la base giuridica del patronato pontificio dell’istituzione attraverso la persuasività delle immagini, Sisto IV commissionò un ciclo maestoso di affreschi che inserirono a pieno titolo l’ospedale nel panorama culturale della città, raccontando la storia dell’istituto fondato da Innocenzo III, sino alla sua coeva ricostruzione.

Calate nell’equilibrio compositivo dell’architettura delle Corsie Sistine, le 99 opere di Pizzi Cannella dialogano mirabilmente con gli affreschi quattrocenteschi, rifuggendo la retorica più ovvia del vittimismo.

L’epica de “Le Migranti”, infatti, abbraccia pure la dimensione concettuale, scegliendo di raffigurare un’umanità invisibile e nascosta. Anche in questo ciclo, la pittura di Pizzi Cannella si presenta come astratta e figurativa allo stesso tempo, come aveva già osservato Achille Bonito Oliva nel 2013.

Nessun volto, niente sguardi né lineamenti, né corpi o incarnati: l’artista lascia ogni fisionomia all’immaginazione. Parallelamente, come un raffinato stilista, si dedica con meticolosa dovizia di particolari alla rappresentazione pittorica dei panneggi, dei disegni, dei tessuti e delle geometrie, dei ricami, creando modelli diversi di abiti che sprigionano all’unisono la forza arcaica di una tenera femminilità. Con una strabiliante diversità di fogge, le vesti celebrano la naturale vitalità dei processi migratori, la libertà di movimento delle creature e, allo stesso tempo, delle culture e delle idee. L’indugio sull’ornato, acceso da colori spesso sfavillanti, evoca la speranza: quella vitalità visionaria che anima coloro che sono alla ricerca di un futuro. Ma dietro la materia e il colore, il segno dell’artista cela il dramma umano del fenomeno dell’emigrazione. Nell’eleganza che singolarmente li contraddistingue, gli abiti dagli orli rarefatti o assenti non sembrano appesi ma deposti su un lenzuolo, fermi, immobili sulla soglia bidimensionale di una superficie grezza. Le tele rettangolari, poste in sequenza seriale, possono dunque essere interpretate come la rappresentazione metaforica della corsia di un ospedale, in cui ciascun’opera evoca l’immagine di un letto, ove un corpo, inconsistente come quello di un fantasma, resta adagiato per poi a svanire. Un corpo senza sostanza né vita, vestito con l’abito più bello secondo i più remoti rituali romani della sepoltura. Quell’abito che, immagina l’artista, “Le Migranti” devono aver “ammucchiato” in fondo all’unico bagaglio che è consentito trasportare sui barconi e che rappresenta per ciascuna

donna l’abbraccio alla vita passata, agli amori passati, alla famiglia scomparsa.

“Nell’arte di Pizzi Cannella – osservava con acume Mario Codognato – il corpo, come misura e bersaglio di tutto, si manifesta […] in un riverbero lirico della sua assenza. Da una parte gli oggetti si antropomorfizzano in scheletri della memoria […] Dall’altra rimangono in attesa di […] una scia umana che ne prenda possesso, che […] li indossi, che ne prefiguri un destino irrealizzabile”. In questa prospettiva, i dipinti di Pizzi Cannella possono essere visti come 99 spettri di migranti che, nel riverbero lirico della loro assenza, animano virtualmente le Corsie Sistine, al punto da essere percepiti essi stessi in modo vivido e coerente. Sottolineano, attraverso il gesto creativo contemporaneo, il significato simbolico radicato nel luogo: quel “significato” che, secondo Kevin Lynch, “costituisce il punto di contatto tra la forma dell’ambiente e il processo di percezione e di conoscenza dell’uomo”.

Così “Le Migranti”, apparentemente risorte nel ricordo di undici secoli di tradizione umanitaria di accoglienza, entrano a far parte di un’epopea millenaria. Confermano le parole dell’artista, ovvero che “dalla cronaca si è passati alla storia”. La mostra, dunque, intesse un dialogo profondo e proficuo con lo spirito del luogo. Un dialogo che rende più vitale lo straordinario patrimonio culturale, materiale e immateriale, del complesso architettonico di Santo Spirito in Sassia, e attraverso una visione dinamica ne rafforza la conoscenza e il grado di percezione.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .

HOSPITALITY AND ART IN THE CORSIE SISTINE DI SANTO SPIRITO IN SASSIA

Renata Cristina Mazzantini

“Every place has its spirit,” wrote Maurus Servius Honoratus in his Commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid, referring to the genius loci that, in the Roman period, was the personification of a spirit representing a place’s identity. The genius loci was considered a supernatural being, a minor deity that embodied the sacrality of a particular site, protected it, and was supposed to be worshipped so as to secure the deity’s favour for local inhabitants. The sentiment of the genius loci has stood the test of time, and even if the spiritual intimacy between people and places has partly been lost, in Rome it can still be perceived, nestled in the urban fabric, even within the artificial landscape of the city, ancient and dense with historical stratifications.

If we reflect back on how powerful the concept of genius loci was in the past, the idea of organizing the exhibition of Pizzi Cannella’s Le Migranti on the edge of the papal city, inside the hospital complex of Santo Spirito in Sassia – and more specifically in the magnificent Corsie Sistine (Sistine Wards) – appears as intriguing as it is appropriate. The Corsie Sistine, which constitute the first example of Renaissance civil architecture in Rome, are two symmetrical arms of a monumental gallery 130 meters long. An imposing architectural volume embellished by 1,200 m2 of frescoes, crowned by a flat wooden ceiling and divided by an elegant Renaissance ciborium.

Despite this extraordinary spatiality, it is not the architectural value but rather the spirit of the place, its historic vocation for hospitality and its symbolic meaning, bound to Christian caritas, that makes Santo Spirito in Sassia an ideal place to display Le Migranti. A cycle of 99 canvases painted by Pizzi Cannella ten years ago, with the aim of stimulating a profound and learned reflection on migration, described not as an emergency but as a historical reality that is indissolubly linked to the theme of hospitality.

Santo Spirito in Sassia certainly is a privileged site of hospitality. Until the 1980s, it performed and passed on its original function as a place of assistance and care for people: first pilgrims, then orphans, and finally the sick.

The current architectural complex stands upon the Schola Saxonum, built at the behest of Ine, King of Wessex, in the 8th century, for the precise purpose of assisting and lodging Anglo-Saxon travellers on pilgrimage in the holy city. There were numerous foreign communities in Rome at the time and the Scholae were charitable institutions, offering food, lodging and even small donations to pilgrims of their particular ethnic group. It should be recalled that, in addition to pilgrims, these hospices also housed the sick and infirm, the poor and homeless, in a challenging promiscuity in which sanitas corporis and salus animae – and thus charitable and therapeutic aims – were constantly intermixed.

In 1198 the Schola Saxonum, which had previously become the hospitalis Anglorum or hospice of the Saxon pilgrims, was transformed by Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) into the “Archihospital” of Santo Spirito in Saxia. With the economic support of the British sovereign John Lackland, the pontiff initiated the construction of an architectural complex to house abandoned or needy children and entrusted its management to the hospitaller order of the Holy Spirit, the first non-military hospitaller order established with an exclusive commitment to caritas.

In the 15th century, hospital reform gradually but ubiquitously replaced charity with medical knowledge. Thus Sixtus IV della Rovere, who was pope from 1471 to 1484, decided to remodel Santo Spirito in Sassia entirely, concluding building work in 1478. To reinforce the juridical foundations of the papacy’s patronage of the institution with the persuasiveness of images, Sixtus IV commissioned a majestic cycle of frescoes that underline the hospital’s importance in the city’s cultural panorama, telling the story of the institute founded by Innocent III from its establishment to its contemporary rebuilding.

Set within the compositional equilibrium of the architecture of the Corsie Sistine, the 99 works of Pizzi Cannella spark a wondrous dialogue with the 15th-century frescoes, spurning a more superficial rhetoric of victimization.

For the epic of Le Migranti embraces the conceptual dimension as well, choosing to portray an invisible and hidden humanity. In this cycle as well, Pizzi Cannella’s painting comes through as abstract and figurative at once, as Achille Bonito Oliva observed back in 2013. No faces, no expressions or features, no bodies or skin colours: the artist leaves any and all physiognomy to the imagination. At the same time, like a refined stylist, he devotes himself with a meticulous wealth of details to the pictorial representation of drapery folds, motifs, fabrics and geometries, embroidery, creating various models of garments that unleash, with one voice, the archaic force of a tender femininity. With an incredible variety of shapes, the pieces of clothing celebrate the natural vitality of migratory processes, the freedom of movement of creatures and, simultaneously, of cultures and ideas. The artist’s focus on ornamentation, lit up by what are often dazzling colours, evokes hope: the visionary vitality that drives those seeking a future. But behind the material and the colour, the mark of the artist conceals the human drama of the phenomenon of emigration. In the elegance that distinguishes them individually, the garments with subtle or absent hems seem to be not hung but rather deposited on a sheet, still, motionless on the two-dimensional threshold of a rough surface. The rectangular canvases, displayed in sequence, can thus be interpreted as the metaphorical representation of a hospital ward, in which each work evokes the image of a bed, where a body, immaterial like that of a ghost, is laid down and then disappears.

A body without substance or life, dressed with one’s most beautiful garment according to the remotest Roman burial rituals. The garment which, the artist imagines, The Migrants must have “stuffed” into the bottom of the one bag passengers are allowed to carry on the perilous Mediterranean crossings, and that for each woman represents the embrace of a past life, past loves, a family vanished.

“In the art of Pizzi Cannella,” Mario Codognato acutely observes, “the body, as the measure and target of everything, is manifested […] in a lyrical reverberation of its absence. On the one hand objects are anthropomorphized into skeletons of memory […] On the other, they sit waiting for […] a human wake that takes possession of them, that […] wears them, that prefigures their unrealizable destiny.” In this perspective, the paintings of Pizzi Cannella can be seen as 99 ghosts of migrants who, in the lyrical reverberation of their absence, virtually animate the Corsie Sistine, to the point of being perceived themselves in vivid and coherent fashion. They underline, through the contemporary creative gesture, the symbolic meaning rooted in place: that “meaning” that, according to Kevin Lynch, “constitutes the point

of contact between the shape of the environment and the process of man’s perception and knowledge.”

Le Migranti, seemingly resurrected in the memory of an 11th-century tradition of hospitality and care, thus take their own place in a millennia-long epic. Further confirmation of the artist’s view that “we have passed from chronicle to history.” The exhibition weaves a profound and fruitful dialogue with the spirit of this place. A dialogue that makes the extraordinary cultural, material and immaterial heritage of the architectural complex of Santo Spirito in Sassia even more vibrant with life, and through a dynamic vision strengthens both our knowledge and our perception of it.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .

PIZZI CANNELLA “LE MIGRANTI” OVVERO L’ABITO PIÙ BELLO DI SPERANZA

Cesare Biasini Selvaggi

Questa mostra de “Le Migranti” l’ho realizzata nell 2015 tutta quanta di seguito. Ma non le

ho mai esposte prima, fintanto che la migrazione era per tutti un fatto di cronaca… Poi c’è

stato come un salto: dalla cronaca si è passati alla storia. Oggi non è più un’emergenza, è

una realtà storica. Ecco perché, dopo quasi dieci anni dalla loro esecuzione, ho deciso di

mostrarle; intanto ne ho viste tante di mostre che parlavano di migranti e migrazioni. Questa

è una piccola, diciamo, anomalia legata molto al mio lavoro. È molto semplice: io credo, sono

pronto a giurarlo, che ognuna de “Le Migranti” porti con sé, nel povero sacchetto che le è

consentito di trasportare in spalla quando monta sui barconi, il suo abito più bello, le sue

scarpe più preziose. Un oggetto che fa parte della sua vita che se arriva, quando arriva, e

dove arriva, avrà con lei. Mentre lo dico mi fa pensare alla fotografia che hanno in galera gli

ergastolani attaccata al muro: è una cosa, una sola, che porta con sé… è il suo non dimenti-

care, il suo abbraccio alla vita passata, ai suoi amori passati, alla sua famiglia scomparsa. Su

questo io ho realizzato questa serie di dipinti, pensando che ognuna de “Le Migranti” ab-

bia ammucchiato in fondo a quel sacchetto di plastica, unico suo bagaglio, l’abito più bello.

Pizzi Cannella, Roma, marzo 2024

Pizzi Cannella è un narratore rabdomantico. Sin dagli esordi, oltre cinquant’anni fa, ha trovato nella pittura la forma della sua prosa che, in questa occasione, descrive gli abiti più belli de “Le Migranti”, il suo ennesimo, nuovo viaggio nella memoria personale che diviene collettiva, e viceversa. All’apparenza solo degli oggetti esemplari, di quelli che appartengono alle cerimonie sociali anzi, per dirla con le parole degli antropologi, alla strategia del dono, gli abiti di Pizzi Cannella sono ancora una volta tessuti nel telaio della memoria, dove la storia scivola lungo fusi appuntiti, da un ordito all’altro, dalla sfera della coscienza e della verifica a quella dell’inconscio collettivo. I loro colori sembrano partoriti dalla notte, quasi affiorati da quelle acque ferali, come evocati da sottili tagli di luce lunare, da colpi di rasoio lanciati nell’oscurità di quel mare ancora più grande per quei migranti e richiedenti asilo che utilizzano la rotta del Mediterraneo centrale per riparare in Europa. Concentrandosi sulla percezione de “Le Migranti” piuttosto che sulla loro iconografia, questo ciclo di 99 tele incarna l’evocazione di un’esperienza: si entra nella mostra come si esce all’alba di ogni mattina, affidandosi al ricordo che non trascura mai la speranza, alla propria immaginazione di origine archetipa rivolta alla ricerca della verità attraverso i territori comuni.

Questo de “Le Migranti” appare come l’epica visione genitiva di un sentimento che ha tutte le stimmate per poter essere considerato imago memoriae. E la memoria, si sa, non ha lineamenti se non quelli che la nostra vita interiore, il nostro inconscio collettivo di junghiana rivelazione gli affidano o colgono dal reale.

Il vestito per Pizzi Cannella è abito (dal latino habitare, “abitare”) in quanto elemento di relazione con lo spazio e le condizioni ambientali contingenti, è abito (da habitus nel senso di “comportamento”, “abitudine”) in quanto passe-partout relazionale con gli altri e, infine, è abito (da habitus nel significato di “assumere un abito”, “virtù dell’animo”) come emblema di affermazione delle qualità spirituali e morali di colei a cui appartiene.

“Su questo io ho realizzato questa serie di dipinti, pensando che ognuna de ‘Le Migranti’ abbia ammucchiato in fondo a quel sacchetto di plastica, unico suo bagaglio, l’abito più bello”, afferma, dunque, Pizzi Cannella, mentre la sua pittura si fa come lente che concentra l’apparenza per infondere, con la propria luce, spessore, sostanza, dignità. La sua opera, prima di tutto, è una questione di etica. Egli riprende la lezione di Aristotele secondo il quale etica deriva più da abito in quanto abitudine, abitare, coabitare, che dalla nozione di norma. È etico quel comportamento che abitua ad abitare insieme, facendone il proprio costume, il proprio abito. Per l’artista, come per Tommaso d’Aquino, quindi, l’abito-habitus rappresenta la libertà, i principi intrinseci dell’azione umana, in quanto esito della ripetizione liberamente decisa di un’azione, contribuendo alla formazione di un agire che diventa agibilità nel tempo e nello spazio, praticabilità del mondo stesso, relazione con gli altri, oltre che con l’origine: Dio, comunque sia inteso.

Ecco il tesoro che ogni migrante ha “ammucchiato in fondo a quel sacchetto di plastica, unico suo bagaglio, l’abito più bello”, ovvero la speranza. E, per dirla con le parole di don Luigi Ciotti, “la speranza non è reato. Non può essere reato sperare di migliorare le proprie condizioni di vita. Senza speranza non c’è vita, ma soltanto sopravvivenza”, senza speranza non c’è agibilità, quindi libertà di esistere, familiarità del sé con il mondo. Non si può essere liberi da soli. Lo sguardo sulle migrazioni di massa si allarga così alla dimensione privata lungo le tele di Pizzi Cannella.

Uno non ha che da guardare le tele de “Le Migranti” per rendersi conto di come gli abiti siano luogo speciale di affioramento dell’identità umana, traducendo nella materia pittorica quella fenomenologia del movimento corporeo teorizzata da Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Potenza, habitus/ abitudine, identità sono i centri intorno a cui orbita la riflessione del filosofo francese: la coscienza non è un “io penso che”, ma un “io abito, assumo un abito, io posso”.

D’altronde, il vestito già nella Bibbia è simbolo d’identità, di dignità di condizione, indicando ciò che si ha nel cuore. È quanto Dio dona ad Adamo e a Eva vestendoli, nei racconti della creazione. Nella Bibbia l’abito conferisce dignità ai re (1 Re 22,30; 2 Re 9,13), ai sacerdoti (Lv 21,10; Sir 50). Cambiare abito poteva significare pertanto cambiare la propria identità, addirittura spirituale, di credo religioso: i cittadini di Ninive “vestirono il sacco, grandi e piccoli” (Gion 3,5).

Gli abiti, quelli più belli, più preziosi, che Pizzi Cannella ha immaginato in quel sacchetto di plastica di fortuna che ciascuna delle sue “Migranti” porta con sé, sono l’esito di una lenta maturazione e di una pittura a volte sontuosa, a volte tumultuosa, spesso per sottrazione, che esalta la capacità di queste vesti di rigenerarsi e sempre esistere, come memoria inventata, falsa, filtrata dalla finzione tipica dell’arte, come luce, colore, spazio, come tende da montare e smontare, spazi in cui ciascuna può eclissarsi, o attraverso cui può mettersi in salvo.

Le tele, gli abiti approntati sul cavalletto interpretano e si interpretano: narrano di sé, del mondo de “Le Migranti”, del loro immaginario nella solitudine, come in un diario privato, intimo e sospeso, che racconta di una nuova, personale mitologia della speranza a cui aggrapparsi con ostinazione. La pittura realizza qui un’estinzione del superfluo, possiede il gusto dell’inquadratura e del taglio essenziale, conservando l’istantanea di abiti che sopravvivono alla finitezza umana, rivelando un passato, un presente e, a differenza dei corpi che li hanno indossati, anche un futuro. Saranno infatti loro, insieme ad altre cose, a raccontare le loro proprietarie a qualcuno quando non ci saranno più.

A trattenerne tracce dei loro corpi, dei loro gesti, dei loro movimenti e delle loro azioni che hanno rivestito, protetto, insieme alle loro aspettative. È La vita delle cose (Laterza, 2009) di cui scrive Remo Bodei, è la vita de “Le Migranti” e dei loro abiti più belli per il tempo che verrà del riscatto dal quel destino-matrigna, che Pizzi Cannella dipinge.

Queste reliquie laiche sono epifanie evocate, tuttavia, non per essere un semplice sostituto della memoria ma, al contrario, per condurre verso un sentimento d’immersione totale, di complicità e simpatia diffusa, verso la freschezza e il profumo di vita di cui sono emblema, verso la verità attraverso i territori del comune sentire. Tanto quanto sono chiamate a fare quelle parole, estensione dei titoli dei dipinti, vergate a colpi di pennello al verso delle tele, sradicate dall’artista dalle pagine di cronache giornalisti che o librarie di anni orsono, quando la storia de “Le Migranti” era ancora cronaca. Se fossimo in ambito musicale, si potrebbe pensare a questo punto a quel valzer lento di campagna che la madre dell’artista gli cantava nei giorni del buio del dolore del corpo o dell’anima, di cui un ritornello recita:

Noi siamo qua e guardiamo alle stelle e alla luna, chissà se per noi non cambi la nostra fortuna.

Se cambia la musica di questo organin, potrebbe di colpo cambiare il destin. Verrà, non verrà, forse è accanto e nessuno lo sa.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .

PIZZI CANNELLA LE MIGRANTI: THEIR BEAUTIFUL DRESSES OF HOPE

Cesare Biasini Selvaggi

I created Le Migranti in 2015, one after another. But I never exhibited them before, while mi-

gration was a news story for everyone… Then there was a leap: from news the story became

history. Today it is no longer an emergency, it is a historical reality. That’s why, almost than ten

years after completing these works, I decided to show them. Meanwhile, I have seen so many

exhibitions about migrants and migration. This is what we might call a small anomaly very

much related to my work. It is very simple: I believe, I am ready to swear, that every one of Le

Migranti carries, in the poor bag that she is allowed to carry on her shoulder while boarding

the barges, her most beautiful dress, and most precious shoes. An object that is part of her

life, and she will have with her if she arrives, when she arrives, and wherever she arrives. As

I say this, it makes me think of the photograph that lifers in jail have attached to the wall: it is

one thing, one thing only, that she carries with her – it is his not forgetting, her embrace of her

past life, her past loves, her missing family. I made this series of paintings about this, thinking

that each migrant has her most beautiful dress piled at the bottom of that plastic bag,

her only baggage.

Pizzi Cannella, Rome, March 2024

Pizzi Cannella is a prophetic narrator. More than fifty years ago, ever since he started, he has found the form of his narrative in painting. On this occasion, his creativity describes the most beautiful clothes in Le Migranti, yet another new journey into a personal memory that becomes collective, and vice versa. What are only apparently exemplary objects, belonging to social ceremonies or rather, in the words of anthropologists, to the strategy of the gift, Pizzi Cannella’s clothes are once again woven in the loom of memory, where history slips along sharp spindles, from one warp to another, from the sphere of consciousness and verification to that of the collective unconscious. Their colours seem to be born out of the night, almost surfaced from those feral waters, as if evoked by subtle cuts of moonlight, by razor strokes into the darkness of that even greater sea for those migrants and asylum seekers who use the central Mediterranean route to find refuge in Europe.

Focusing on the perception of Le Migranti (femail migrants) rather than on their iconography, this cycle of 99 canvases embodies the evocation of an experience: one enters the exhibition as one leaves at dawn each morning, relying on memory that never neglects hope, on one’s imagination of archetypal origin turned to the search for truth across common territories.

Le Migranti is the epic possessive vision of a feeling that has all the signs needed to be considered imago memorize. And memory, as we well know, has no features other than those that our inner life, our collective unconscious of Jungian revelation, entrusts to it or grasps from reality.

For Pizzi Cannella the Italian abito – our “dress” – comes from the Latin habitare, “to inhabit.” That brings us to the origin of the Middle English word habit, denoting dress or attire, an element of relationship with space and contingent environmental conditions, i.e. abito (from habitus in the sense of “behaviour,” “habit”) as a relational passe-partout with others. Finally, abito (from habitus in the meaning of “to assume a habit,” “virtue of the soul”) is an emblem of affirmation of the spiritual and moral qualities of the one to whom it belongs.

“That is the basis of this series of paintings, thinking that each of Le Migranti has piled at the bottom of that plastic bag, her only baggage, the most beautiful dress,” says Pizzi Cannella, as his painting becomes a lens that concentrates appearance to infuse depth, substance, and dignity with its own light. First and foremost, his work is a matter of ethics. He adopts Aristotle’s lesson that ethics derives more from habit as habit, dwelling, cohabitation, than from the notion of norm. Ethical behaviour is that which habituates one to inhabit together, making it one’s custom, one’s habit. For the artist, as for Thomas Aquinas, therefore, habit-habitus represents freedom, the intrinsic principles of human action. It is the outcome of the freely decided repetition of an action, contributing to the formation of an action that becomes flexibility in time and space, practicability of the world itself, relationship with others, as well as with the origin: God, however it is understood.

Here is the treasure that every migrant has “piled at the bottom of that plastic bag, her only baggage, the most beautiful dress”: hope. And, in the words of Don Luigi Ciotti, “hope is not a crime. It cannot be a crime to hope to improve one’s life. Without hope there is no life, only survival,” without hope there is no flexibility, hence freedom to exist, familiarity of the self with the world. One cannot be free alone. The gaze on mass migration thus widens to the private dimension on Pizzi Cannella’s canvases. One has but to look at the canvases of Le Migranti to realize how clothing is a special outlet for the emergence of human identity, translating into pictorial matter the phenomenology of bodily

movement theorized by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Power, habitus/habit, identity are at the centre of the French philosopher’s reflection: consciousness is not an “I think that,” but “I dress, I assume a habit, I can.” Then again, even back in the Bible, clothing is a symbol of identity, of dignity of status, indicating what is in one’s heart. It is what God gives to Adam and Eve by clothing them, in the creation stories.

In the Bible, clothing gives dignity to kings (1 Kings 22:30; 2 Kings 9:13), to priests (Lev 21:10; Ecclus 50). Changing clothes could therefore mean changing one’s identity, even spiritual, religious beliefs: the citizens of Nineveh “dressed in sackcloth, great and small” (Jon 3:5).

Clothes, the most beautiful, most precious, that Pizzi Cannella has imagined in that makeshift plastic bag that each of his migrants carries, are the outcome of a slow maturation and painting sometimes sumptuous, sometimes tumultuous, often depicted by subtraction, that exalts the capacity of these garments to regenerate and exist forever, as invented memory, false, filtered by the fiction typical of

art, as light, colour, space, as tents to be assembled and disassembled, spaces in which each can eclipse itself, or through which it can save itself. The canvases, the clothes laid out on the easel, interpret themselves and each other: they narrate their own stories, the world of Le Migranti, their imagery in solitude, as in a private, intimate and suspended diary that tells of a new, personal mythology of hope to stubbornly cling to.

Painting here achieves an extinction of the superfluous, possessing a taste for framing and essential cutting, preserving the snapshot of clothes that survive human finiteness, revealing a past, a present and, unlike the bodies that wore them, also a future. For it will be they, along with other objects, that will tell their owners’ stories to someone when they are gone. That is how traces of their bodies, their gestures, movements and actions that they have clothed, protected, along with their expectations will be retained. That is La vita delle cose (Laterza, 2009) that Remo Bodei writes about. Pizzi Cannella paints the life of Le Migranti and their finest clothes for the coming time of redemption from that stepmother, fate.

These secular relics are epiphanies evoked, not, however, to be a simple substitute for memory but, quite the contrary, to lead toward a feeling of total immersion, of complicity and widespread affinity toward the freshness and fragrance of life that they signify, toward truth through the territories of common feeling. That is what those words are required to do, extensions of the titles of the paintings, penned with brushstrokes on the canvases, eradicated by the artist from the pages of newspaper or book chronicles of years ago, when the story of Le Migranti was still being told. If we were in the realm of music, one might think of that slow country waltz that the artist’s mother used to sing to him in the dark days of pain of body or soul, where one refrain reads:

We are here, and we look to the moon and the stars, who knows if our fortunes might change. If this little organ’s music changes, destiny might do the same. It will come, it won’t come, maybe it’s next door and what could it become.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .

LE NOVANTANOVE “MIGRANTI”

Rossella Fumasoni

Dal mare in tempesta, dall’attraversamento del deserto, dalle finestre di Tunisi né chiuse né serrate, notturne o mattiniere che siano, le 99 vesti femminili di Pizzi Cannella finalmente sono apparse.

Erano in attesa, hanno aspettato dieci anni arrotolate al buio.

Di tutto il lavoro di Pizzi Cannella questa è l’impresa più sentimentale di tutte.

Le 99 migranti sono una piccola folla di cittadine del mondo e della storia, provenienti da continenti e tempi diversi.

Afghane, Armene, Congolesi, Siriane, Cinesi, Ivoriane, Iraniane, Spagnole, Greche, Italiane, Portoghesi e ancora e ancora.

Si, c’è l’attuale ma anche giorni sparsi in più secoli.

Pizzi Cannella le ha evocate una per una, estraendole dalla sua pittura.

Odissea femminile di voci sussurrate, cantate, tormento e invocazione, rovesci di fortuna, inaspettata salvezza, superamento e gioia.

Sono talmente tanti gli echi e le voci che gli abiti portano con loro, che è quasi impossibile aggiungere altro.

99 spostamenti, suggeriti, siglati da un profumo di parole scarne e accenni di racconti interrotti. Voci nel sonno. Biglietti di addio e di arrivederci.

A ogni padrona dell’abito viene restituito il suo sguardo sul mondo, lo scintillio di un pensiero.

Gli alberi d’Africa, il bianco trasparente del latte materno, l’amore di una figlia per suo padre, gli uomini più cari e quelli più cattivi, un’amica da abbracciare stretta, la fame e la sete, ballare con una gamba sola gareggiando con un centopiedi; può essere tutto qui tra “Le Migranti”.

Evocate tutte e 99, parlano ogni lingua; se ti avvicini puoi sentirle.

Tra sorpresa e pericolo imminente, tra solitudine e dedizione eroica, cura tenacia, fuga, perseveranza, nostalgia, perdita.

È un racconto lambito, sfiorato, che trova spazio nel retro di tutte le tele, tutte e 99, un racconto pronto sempre a sfuggire, in un turbinio di svariatissimi indizi: nomi, riflessioni amare o amorose, nomi di alberi e poeti.

Pizzi Cannella vuole restituire i suoi vestiti alle legittime proprietarie, chiamandole a sé una alla volta per nome, tutte e 99, perché a ogni vestito corrisponde un nome di donna.

Un fiume di 99 corpi vivissimi che sono il corpo stesso della sua pittura, forte della volontà di poter aggiustare, accomodare, superare ogni difficoltà, rimediare a ogni sopruso, colmare ogni distanza, asciugare ogni lacrima; questa è la volontà che la pittura porta con sé.

Il vestito di Pizzi Cannella è sempre stato un sudario, la camiciola della strega prima d’essere bruciata, l’abito cencioso di Giovanna d’Arco, quello della malata di tisi sfuggita al sanatorio che corre tra i boschi, della naufraga perduta nel Mar dei Coralli, che in un dormiveglia di febbre e di desiderio di latte si trafigge con spille magnifiche il cuore, gioielli del suo amore ormai perduto. Attrae ogni storia possibile.

Il vestito se ne sta sulla tela nuda al sole ad asciugare, scampato al naufragio, resta lì Sospeso per amore, qui ancora di più.

Ancora per amore restano sospese le vesti de “Le Migranti”, in quell’incanto necessario, per la scommessa in un altrove, dove la veste possa stendersi su un letto, dove finalmente possa smettere di avere paura.

È il letto della pittura stessa.

Letto di Regina di Santa, della Madonna in persona, ma anche di Spia, di Assassina, di Puttana, di Mendicante incinta, di tutte le gloriose protagoniste della storia e delle sventurate; è un letto di tela nuda che le accoglie.

Tutte loro comunque vada, si portano dietro il loro vestito più bello.

Scrive Pizzi Cannella dietro a Maddalena: “Portati un vestito a fiori ne avrai bisogno”.

L’abito preferito di ognuna, portato dall’Africa Bianca, dall’Africa Nera, Cina, Urali, Madagascar.

L’abito prediletto di Maria, dalle profondità della baia di Gibilterra dove s’inabissò a bordo del piroscafo Utopia nel 1891.

“Le Migranti” si attengono al protocollo ferreo e inviolabile di Pizzi Cannella: abito visibile, corpo invisibile, il corpo resta avvolto nel mistero, il volto, le teste, le braccia, le gambe,

i piedi leggeri, i colli, le spalle, tutte le loro 198 mani.

Perché l’abito così fatto, vuoto, le contempla tutte, le donne, le bambine, le anzianissime signore. Ognuna così lo potrà indossare prima o poi.

È fatto così il vestito di Pizzi Cannella.

L’abito è di tutte e di nessuna, è senza documenti, ha sempre eluso la sorveglianza, ma in questa impresa non è andata proprio così. Il protocollo è stato violato.

Abbiamo i nomi, i giorni, latitudine e longitudine, mari, rimpianti, imprecazioni e sospiri.

L’abito però non può sfuggire alla pittura, non può andarsene troppo in giro a raccontare i suoi segreti. Non si deve sapere che la pittura è così viva, che è nata e non muore, rinasce

ogni giorno, in luoghi diversi, da mani diverse e respira respira respira.

La pittura è il respiro del mondo, l’unico modo conosciuto per non morire.

Può essere d’aiuto visto che vogliono farci morire e basta.

Si vocifera che la pittura rivuole indietro il vestito di Pizzi Cannella, che vorrebbe rimescolarlo al suo impasto e farlo sparire.

La pittura si occupa di vesti dalla notte dei tempi e ne reclama il possesso.

Deve essere per questo che le 99 migranti si sono nascoste così a lungo, ma ora basta, vogliono mostrarsi.

Nate dal desiderio di Pizzi Cannella di accogliere tutte le sue madri, le madri del nuovo che verrà, restituendogli i loro vestiti.

L’artista restituisce alle donne e alle bambine del mondo, a cui appartengono, i vestiti presi in prestito da decenni. Tutto si rimescola.

Il mondo si rimescola da che è mondo e non si può fermare.

Rimescola le sue 99 carte in un gioco molto più grande di tutti noi.

“Le Migranti” è un inno alla volontà delle donne di avanzare, di combattere la paura, la cattiva sorte senza arretrare di un passo.

Migrante, Ragazzina, Danseuse, Adultera, Incarcerata prossima al plotone d’esecuzione, non c’è classificazione o categoria che non sia suggerita e infranta qui.

La veste è infaticabile, non conosce requie, ed è un balletto di 99 Ètoile.

Il pittore le ama tutte, le ama e le insulta, le prende a male parole e piange con loro.

Pizzi Cannella cerca l’Eretica, la Decapitata, la Prediletta, la Reclusa in una gabbia nella foresta pluviale. Sua madre Assunta da bambina, che guarda la neve nel 1928 a Rocca di Papa.

Ma Pizzi Cannella ci restituisce o no i volti sorridenti o adirati di tutte le vesti svuotate dai corpi, dipinte in questi decenni?

Restituisca l’artista le lunghe braccia, le mani, le dita, gli occhi neri e caldi mai dipinti.

Dove sono tutte?

Qualche occhio sì, è stato già riconsegnato da tempo nei suoi dipinti, ma di labbra, di nasi, d’orecchie, capigliature, piedi, gambe, schiene, seni e ombelichi, dell’interezza dei corpi anche qui nelle 99 Migranti sì c’è traccia palpabile, ma sempre invisibili sono.

Eccolo qui il fiume di 99 corpi invisibili delle legittime proprietarie degli abiti di Pizzi Cannella, quel fiume che è il nostro cuore, che batte e respira.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .

THE NINETY-NINE “MIGRANTI”

Rossella Fumasoni

From the stormy sea, from crossing the desert, from the windows of Tunis neither closed nor shut, whether night or morning, Pizzi Cannella’s 99 women’s dresses have finally appeared.

They were waiting, they waited ten years rolled up in the dark.

Of all Pizzi Cannella’s work, this is his most sentimental undertaking.

The 99 migrants are a small crowd of citizens of the world and history, from different continents and times.

The women are Afghan, Armenian, Congolese, Syrian, Chinese, Ivorian, Iranian, Spanish, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and on and on.

Yes, there is the present but also days scattered over several centuries.

Pizzi Cannella has evoked them one by one, extracting them from his painting.

A female odyssey of voices whispered and sung, torment and invocation, reversals of fortune, unexpected salvation, overcoming and joy.

The clothes carry with them so many echoes and voices that it is almost impossible to add anything else.

99 transfers, suggested, sealed by the scent of sparse words and hints of interrupted tales. Voices in sleep. Notes saying farewell and goodbye.

Each of the dresses’ owners is given back her view of the world, the sparkle of a thought.

The trees of Africa, transparent white breast milk, the love of a daughter for her father, the dearest and the meanest men, a friend to hug tightly, hunger and thirst, dancing with one leg competing with a centipede; it can all be found here among Le Migranti.

All 99 are evoked, they speak every language; you can hear them if you get close enough.

Between surprise and imminent danger, between loneliness and heroic dedication, care, escape, perseverance, nostalgia, loss.

It is a story barely touched, brushed against, one that finds space on the back of all the canvases, all 99 of them, a story that always eludes us, in a whirlwind of various clues: names, bitter or loving reflections, the names of trees and poets.

Pizzi Cannella wants to return her clothes to their rightful owners, calling to them one at a time by name, all 99 of them, because each dress corresponds to a woman’s name.

A river of 99 living bodies that are the very body of his painting, strong in the will to adjust, accommodate, overcome every difficulty, remedy every abuse, bridge every distance, wipe away every tear; that is the will that painting carries.

Pizzi Cannella’s dress has always been a shroud, the witch’s gown before she was burnt, the ragged dress of Joan of Arc, that of the consumptive patient who escaped from the sanatorium and ran through the woods, the shipwrecked woman lost in the Coral Sea, who in a sleep of fever and longing for milk, pierces her heart with magnificent pins, jewels of her lost love. Enticing every possible story.

The dress lies on the bare canvas in the sun to dry, having escaped shipwreck, it remains there Suspended for love, here even more so.

Still, for love, the clothes of Le Migranti remain suspended, in that necessary enchantment, for the wager elsewhere, where the dress can lie on a bed, where it can finally stop being afraid. It is the bed of painting itself.

Bed of the Sainted Queen, of the Madonna herself, but also that of Spy, of Murderess, of Whore, of Pregnant Beggar, of all the glorious as well as the unfortunate protagonists of history; they are welcomed by a bed of bare canvas.

All of them, however they go, take their most beautiful dress with them.

Pizzi Cannella writes of Mary Magdalene:

“Bring a flowery dress, you will need it”.

Each one’s favourite dress, brought from White Africa, Black Africa, China, the Urals, Madagascar.

Mary’s favourite dress, from the depths of the Bay of Gibraltar where she sank aboard the steamer Utopia in 1891.

Le Migranti adhere to Pizzi Cannella’s strict and inviolable protocol: a visible dress, body invisible, the body remains shrouded in mystery, the face, the heads, the arms, the legs, the light feet, the necks, the shoulders, all their 198 hands.

Because the dress thus made, empty, contemplates them all, the women, the little girls, the old ladies. Each one can wear it like this sooner or later.

This is how Pizzi Cannella’s dress is made.

The dress is everyone’s and no one’s, it is undocumented, it has always evaded surveillance, but in this enterprise, it did not. Protocol was violated.

We have names, days, latitude and longitude, seas, regrets, curses and sighs.

The dress, however, cannot escape painting, it cannot go around telling secrets. It must not be known that painting is so alive, that it is born and does not die, it is reborn every day, in different places, by different hands and it breathes, it breathes, it breathes.

Painting is the breath of the world, the only known way not to die.

It can help since all they want us to do is die.

It is rumoured that painting wants Pizzi Cannella’s dress back, to mix it with his colours and make it disappear.

Painting has been dealing with clothes since the dawn of time and claims possession of them.

That must be why the 99 migrants have been hiding for so long, but no more, now they want to be seen.

Born of Pizzi Cannella’s desire to welcome all his mothers, the mothers of the new that is coming, by returning their clothes to them.

The artist gives back clothes borrowed for decades to the women and girls of the world to whom they belong. Everything is reshuffled.

The world has been shuffling for as long as it has been alive and cannot be stopped.

It shuffles its 99 cards in a game much bigger than all of us.

Le Migranti is a hymn to the will of women to advance, to fight fear and bad luck without retreating a step.

Migrant, Little Girl, Danseuse, Adulteress, incarcerated next to the firing squad, there is no classification or category that is not suggested and broken here.

The dress is tireless, knows no rest, and is a ballet of 99 Ètoiles.

The painter loves them all, he loves them and insults them, he mocks them and cries with them.

Pizzi Cannella searches for the Heretic, the Beheaded, the Beloved, the Recluse in a cage in the rainforest. His mother Assunta as a child, watching the snow in 1928 in Rocca di Papa.

But does Pizzi Cannella return the smiling or angry faces of all the robes emptied of bodies, painted in these decades, or not?

Does the artist return the long arms, the hands, the fingers, the warm black eyes that were never painted.

Where are they all?

Yes, a few eyes have long since been returned to his paintings, but there is a palpable trace of lips, noses, ears, hair, feet, legs, backs, breasts and navels, the entirety of the bodies, even here in the 99 Migrants, but they are still invisible.

Here is the river of 99 invisible bodies of the legitimate owners of Pizzi Cannella’s clothes, that river which is our heart, beating and breathing.

© studio_i2 .

© studio_i2 .